“A person’s success in life can be measured by the number of uncomfortable conversations he or she is willing to have.” – Tim Ferris

🪄Keystones:

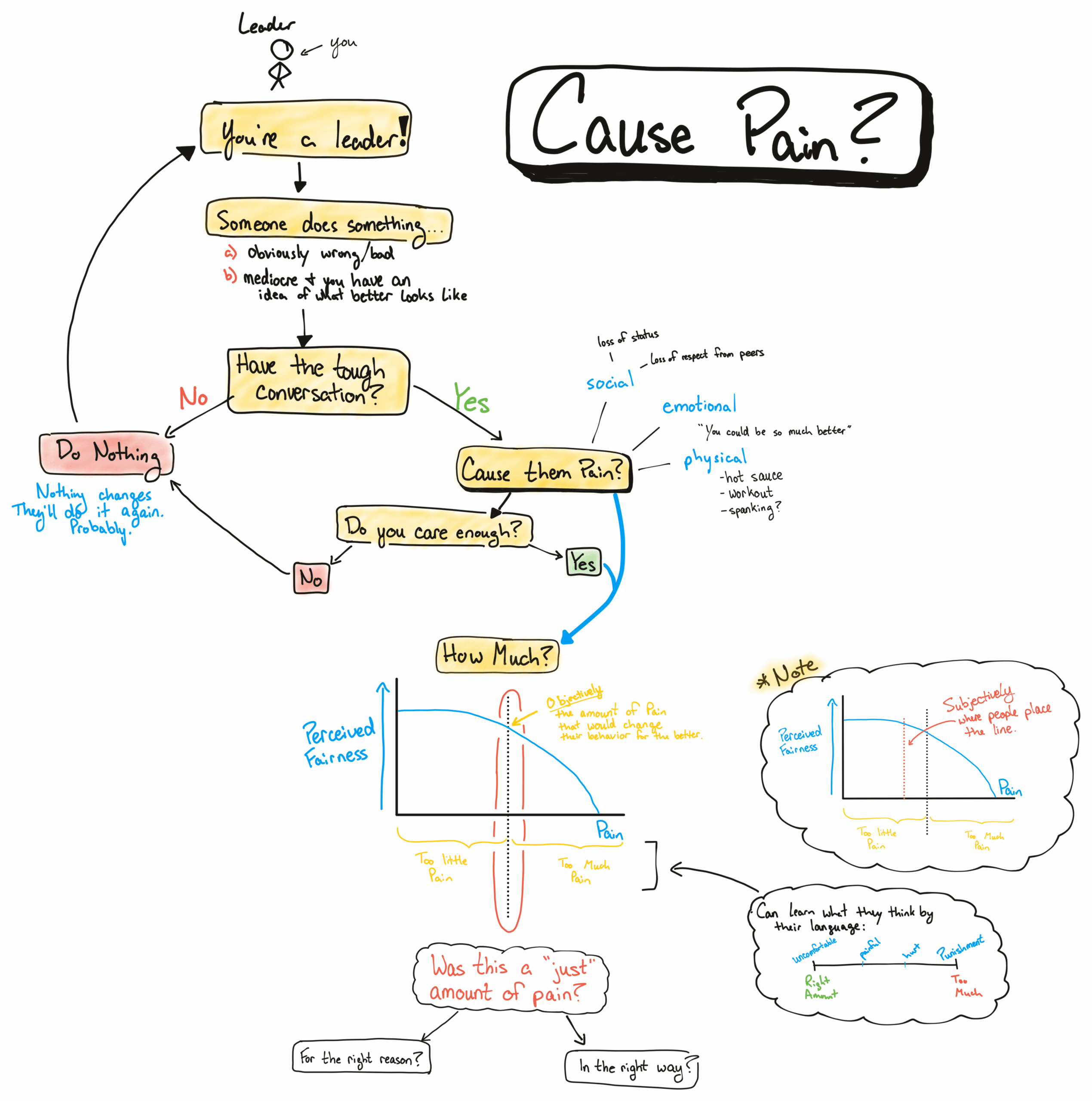

- People struggle to lead others because they don’t want to cause them pain. Pain has varying degrees. There is the mild ‘discomfort’ and the intense ‘punishment’ kinds of pain, which must be married to the behavior you are trying to influence.

- The degree of pain you cause must correlate to inciting the desired behavior change—the one that leads to the better version of them.

Hesitations about causing others pain can be broken down into two pathways: is this amount of pain justified and did I do it in the right way. In other words, was the pain caused in the right way and for the right reasons.

Pain For the Right Reasons

The only reason you need to cause someone discomfort is believing you know what a better version of them might look like. Take the risk of being wrong and share with them. People, especially high-performing people, rarely get any feedback. Most of their lessons learned were from self-reflection and self-analysis. For example, consider the leader of a company. How much critical do you think he/she is getting? How many people are willing to disagree with them?

Thus, how much more valuable then are those individuals that do challenge their thinking? It betters the company and the leader. These leaders long for people willing to challenge their thinking.

Always be attempting to give others the gift of feedback, but check your intentions.

As long as the other person believes you care about them and are well-intentioned, they will receive the pain/lesson/idea more openly, and they’ll forgive the times where your feedback was ineffective to unhelpful.

What Better Them Might Look Like

Before we get into the ‘right way’ of causing someone pain, you must come up with ideas of what better them looks like. Here are the questions I take stabs at:

What does the better version of them look like? How do I help them get there?

On the team level it’s “what does a better version of this team look like?” And “How do I help us get there?” Additionally, if you’re the leader you’re asking, “What is the best direction (read: goal) for us to head towards?”

The leader must be assessing all three and attempting to answer all three. Take care of the people and they will take care of the rest. Give clear purpose and direction so they can help you steer the ship. Give them a North Star to aim at.

The Right Way?

Alright, let’s say you have a member of that team who isn’t measuring up. Maybe they missed a deadline, are shirking work, are ineffectively spending their work time, etc.—regardless, they are doing something that is not the best version of themselves (read: not what they are capable of). Or, maybe it’s a social blunder. They yelled at a coworker, told an inappropriate joke, make others feel uncomfortable, act narcissistically, are perpetually pessimistic, the list goes on.

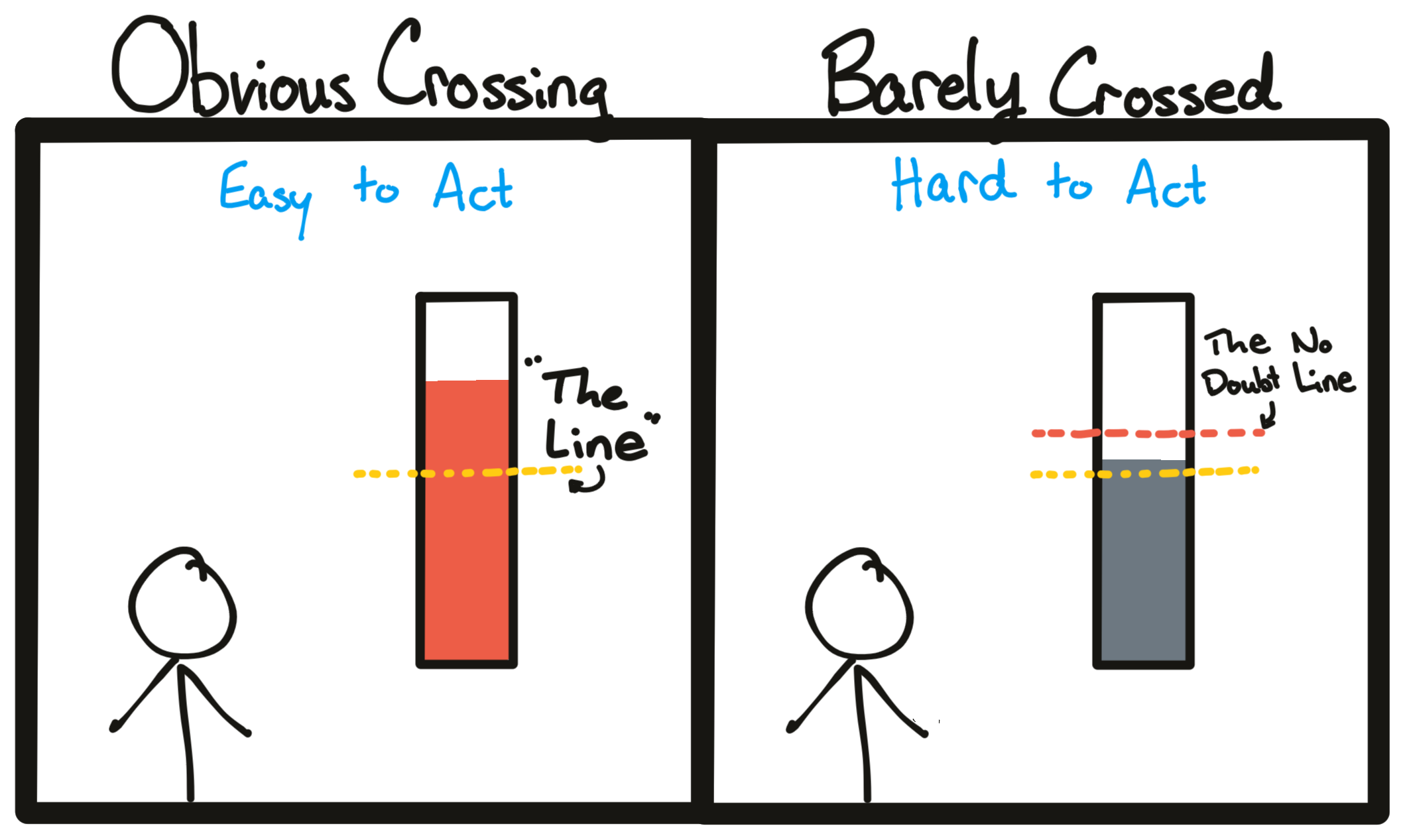

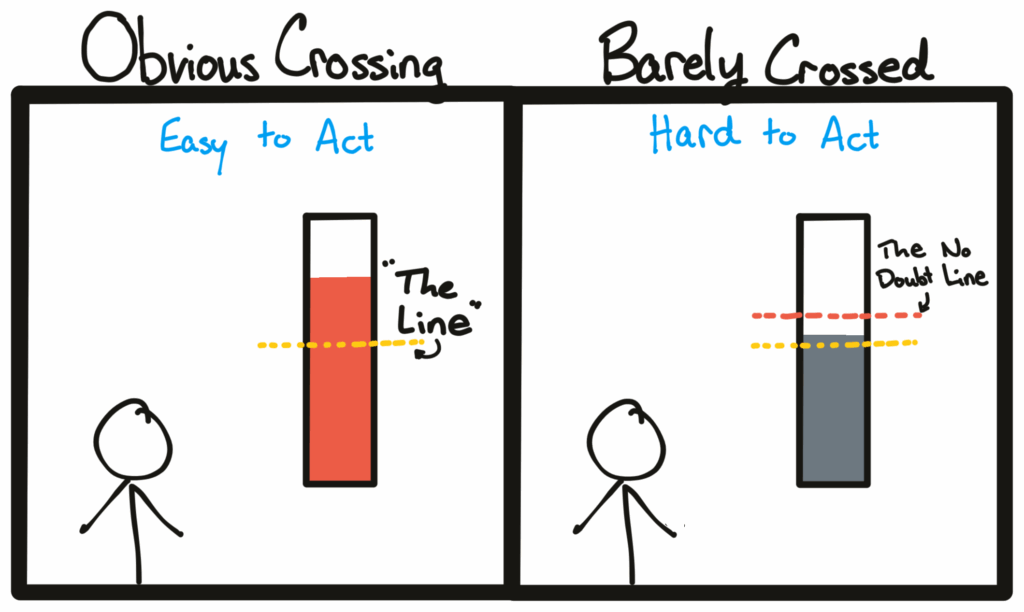

Some flaws are fatal. Some require an immediate removal from the company. Those are the easy mistakes to punish. They cross a usually well-defined threshold set by your company.

Line Nudgers

Those hovering near the line are the hardest to talk to. You second-guess yourself—What if I’m misreading the situation? What if I don’t have the full picture? The uncertainty makes it easier to stay silent. But in the end, it’s better to have said something and been wrong than to have not cared enough to say anything at all.

“A person’s success in life can be measured by the number of uncomfortable conversations he or she is willing to have.” – Tim Ferris

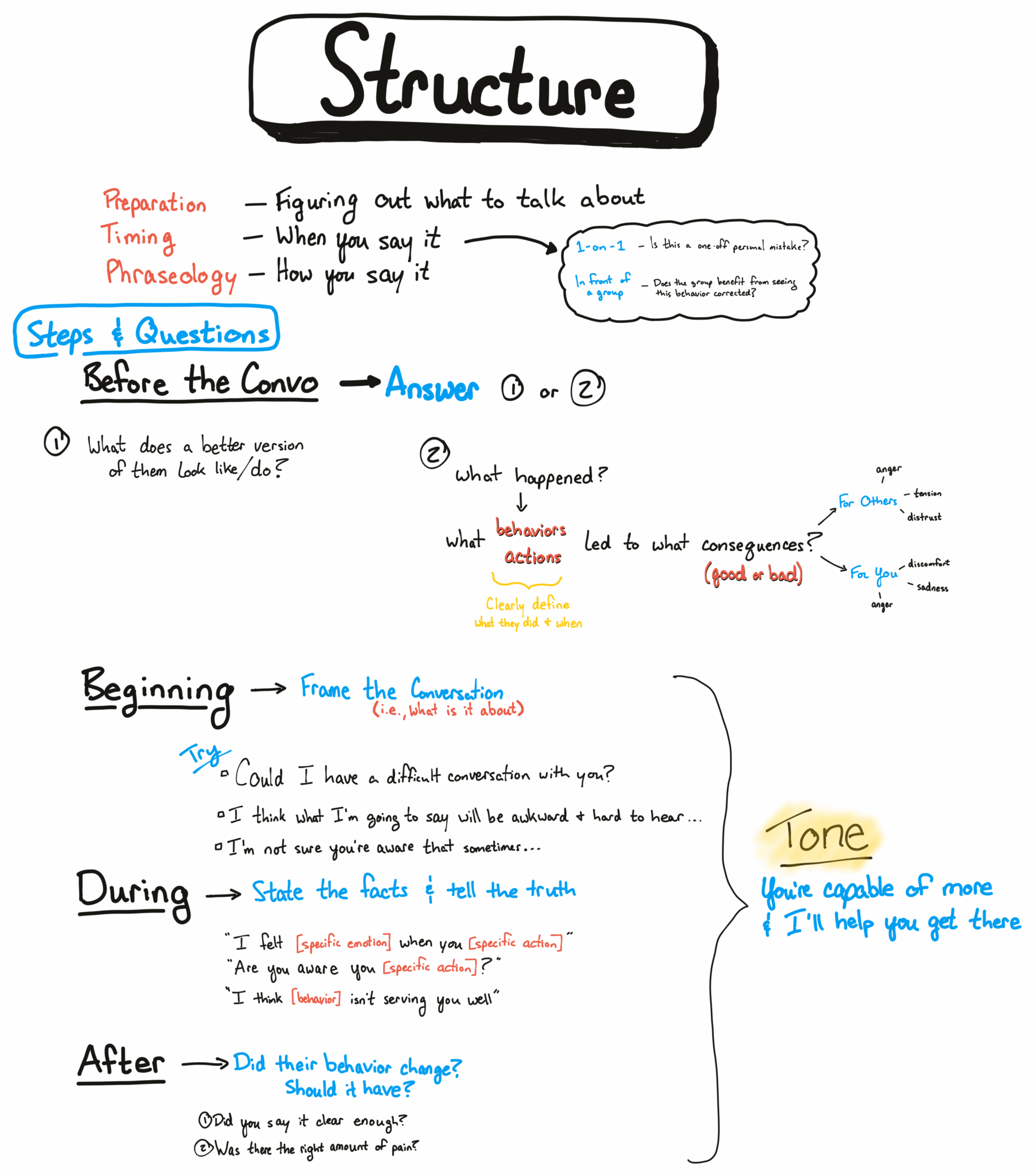

The Right Way: Figuring Out What to Say

The most helpful thing for me in terms of beign able to have more of these conversations was hearing the phrases others used to start the conversation and deliver difficult points during the conversation. Above are a few examples that I like.

Usually you know what to say but not how to say it. Create a repository of phrases that feel like they’re the appropriate level of intensity or seriousness for what you want to say.

Ideally, the first time you notice a behavior that you find unacceptable—er, that’s too strong of a word—a behavior that isn’t helpful to them or the team, pull them off to the side and say something about it one-on-one.

In the military, this is very common so it never bothered me much to tell someone I wanted to speak with them. In the civilian world, this is less common so it seems so serious but it doesn’t have to be. Make the statement casual without expressing anything on your face and try, “Could I talk with you?” The other version of “Could I speak with you?” sounds more formal and serious so I intentionally use the word “talk”.

Prior to this moment you should have already identified 1) the specific behavior/action in question and 2) the effects of that action on you and/or others.

If this one one-on-one conversation doesn’t work, have the talk with another leader present. Let them see that your perspective about their actions isn’t yours alone. The group at large believes the behavior is not good for the group.

Timing

In a perfect world, these conversations would happen as close to the moment as possible. The main reason they often don’t is simply not knowing how to say what needs to be said, especially if it’s your first time addressing this kind of behavior, or not yet having built the personal skill and confidence to handle difficult conversations. With practice, these moments become less daunting and much easier to navigate.

Following the framework, “when you did [specific action] it [specific consequence]” will set you up for success. If you are not certain and haven’t thought through what you want to say mention that at the beginning to frame the conversation: “A part of me feels that when you…” or “I haven’t had enough time to think through how to say this yet but I wanted to talk to you about…”

Final Thoughts

Correcting someone is actually an act of care. Saying something like, “I don’t think this behavior is really helping you—or the people around you,” comes from a place of wanting the best for them. The truth is, the reason we avoid tough conversations isn’t because we’re too kind—it’s usually because we either don’t care enough or we let empathy turn into an excuse. Kim Scott talks about this as ruinous empathy—when you’re more worried about how your honesty will make someone feel than about giving them the feedback they really need. In the end, that’s not caring for them. That’s caring for your own discomfort.

“Regard your soldiers as your children, and they will follow you into the deepest valleys; look upon them as your own beloved sons, and they will stand by you even unto death. If, however, you are indulgent, but unable to make your authority felt; kind-hearted, but unable to enforce your commands; and incapable, moreover, of quelling disorder: then your soldiers must be likened to spoilt children; they are useless for any practical purpose.”― Sun Tzu, The Art of War